The chimera hypothesis: A short history of the first experimental chimera

As far as I know, there is no analogon to our plant in nature, no organism, which consists of one half of one species and one half of another. Hans Winkler, ‘On Graft Bastards and Plant Chimeras’, 1907

Written by Amy Hinterberger & Sarah Kowalski

How did the Chimera monster end up lending her name to a series of experimental practices and organisms in the life sciences? Many of us know the term ‘chimera’ from Greek mythology, referring to the Chimera monster of triple animal origin. But many of us do not know why that term has been so significant in the life sciences, and why it is still used in many areas of biology, such as stem cell science. Below we chart out a small part of the story of how the Chimera ended up lending her name to a distinctive kind of composite organism.

While more well-known for coining the term ‘genome’, it was German botanist, Hans Winkler who first introduced the term ‘chimera’ to the field of experimental biology in the early 20th century. Before this time there had been various speculations in botany about curious plants that did not fit fully with the then prominent ‘graft-hybrid hypothesis’ which spoke of the biological origin of such plants like the Citrus Bizzarria or the L. Adamii. These plants were noted and discussed in 16th and 17th century Europe, but it was only after Winkler’s debut discovery in the 1900s that they were later categorized as plant chimeras. Winkler’s research on grafting two different species of plants Solanum lycopersicum (tomato plant) and Solunum nigrum (nightshade) created an unexpected hybrid-type plant which came to be known as the first recognized plant chimera.

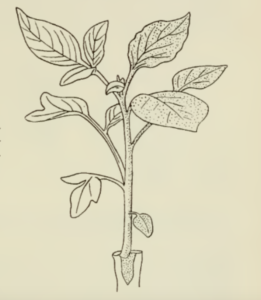

This image, the first of its kind, was presented by Winkler at a meeting of the German Botanical Society in Dresden in 1907.

Winkler’s illustration of his chimera plant, Über Pfropfbastarde und pflanzliche Chimären”, 1907

The committee in Dresden was captivated by this image of Winkler’s curious experimental creation and asked for a paper reporting his research on the topic, a paper, which Winkler was not intending to write upon arriving to Dresden that year.

Due to the large interest in the topic he published his Über Pfropfbastarde und pflanzliche Chimären, or On Graft Bastards and Plant Chimeras paper in 1907. It contains the first recorded use of the term chimera to describe an organism clearly displaying the traits of two different plant species. In the text he explains that he was interested in pursuing research in this topic because another researcher, Eduard Strasburger, had been questioning the correctness of the ‘graft-hybrid hypothesis’ that was prominent in botany at the time and had suggested that there was more to discover in this field of research.

The graft-hybrid hypothesis supported the idea that a new plant created from grafting two different species of plants is somewhat of an offspring of the two species: it displays characteristics of both its parent species in a mixed way. Thus it is called a hybrid. However, the chimera was different. Winkler argued that it is best to think of the creation’s name-sake, the mythological Chimera monster that was part lion, part goat, and part snake. Like the Chimera monster, a biological chimera is an organism that has distinct tissues of its parent species. It is not a new mixture of a species’ characteristics, rather it is an organism that shows distinct species “lying next to each other” in one organism.

The fact that the characteristics of the two parent species were not mixed around the plant but that there was a clear side-by-side division of the two characteristics is what made Winkler see his plant as something different that deserved a new name, something that could not be called a graft hybrid:

“As far as I know, there is no analogon to our plant in nature, no organism, which consists of one half of one species and one half of another – apart, perhaps, from occasional sectoral bastards, perhaps – so that the only analogon left are mythical creatures like the Centaurs, who were half man, half horse, or the Chimera that was (…) I have therefore taken the liberty, in order to give a brief unambiguous description of the category of completely new organisms that has arisen with our plant, to call them, in short, plant chimeras, and so I shall henceforth refer to our plant as the Chimera Solanum nigro-lycopersicum.”

Winkler’s research fit well with the times, as his chimera hypothesis was taken up by multiple researchers who all were able to reproduce his findings (some using different species of plants than Winkler initially used), confirming the existence of the plant chimera.

Coming back to the image from Winker’s paper, we can clearly see this chimeric nature of his tomato-nightshade plant. The plant is divided down the middle by its genetic composition. On the left, in pure white, we can see that half of Winkler’s chimera is a tomato plant, whilst on the right, dotted, this plant has tissues of nightshade. The plant is split in half, containing both Solanum lycopersicum and Solunum nigrum in one organism.

It gets even more fascinating when Winkler points out that he found three types of leaves on his chimera plant: those of pure tomato (C) that could be visible on the left ‘tomato’ side of the plant, those of pure nightshade (C) found on the right ‘nightshade’ part of the plant, and those that are both tomato and nightshade (B) found down the middle of the plant.

Hans Winkler, Über Pfropfbastarde und pflanzliche Chimären, 1907. Illustration: Leaf B depicts this crucial side-by-side characteristic of the chimera plant.

This is another image from Winkler’s 1907 paper that shows this phenomenon. Leaf B depicts this crucial side-by-side characteristic of the chimera plant. Winkler took one of these split-down-the-middle leaves with him to Dresden.

Winkler concludes his paper by shortly explaining how his chimera is not a twin, that in his curious plant one can clearly see a combination of two ‘different individuals’. He states that his chimera is a ‘complete novelty’ and more research into its true nature has to be done. Thus, he opened a new field of study in botany that would eventually be used and carried forward in zoology, embryology and studies of mammalian development.

While the above story focuses on the first use of the term chimera in botany – chimerism, as a term and concept was also eventually used in classic embryology, developmental biology, and carried through to the most current stem cell science of today (Hinterberger 2018). Our project, Biomedical Research and the Politics of the Human, provides a historical account of experimental chimerism as we are tracing the emergence of the ‘chimera’ concept in botany to its expansion into zoology and mammalian biology, with a primary focus on chimeric mammals in 20th and 21st century. Considering the chimera concept in this way enables us to reveal the hidden history of how chimeric organisms have been used in scientific research to gain a better understanding of organisms and to explore the research practices and norms that have shaped science for many decades.

The chimera concept continues to grip social, cultural and scientific imaginations, especially in the 21st century where the life sciences are bringing into being new associations between species and organisms, individuals and groups, humans and non-humans. The chimera, and the concept of chimerism, continues to be held up as a mirror for humanity’s relationship with science. The Chimera monster is often invoked as a spectre of fear for critics of a bioscience run wild across species boundaries. But she is also held up as the great biological equalizer, as you and I (and all animals) can be considered composite life forms sustained by a range of multispecies relations living inside us. All biological life is a form of chimeric and composite life.

However, what we have found in our research within this project, and especially our focus on the history of chimerism in biology, are the hidden multiple and significant contributions the chimera concept has made to biological thought and practice, and how it has come to shape our social world in significant ways. Excavating some of the first uses and depictions of the chimera concept in biology shows us how researchers have used it in variety of ways to make sense of biological life, along with shaping how we organize and govern research on health and disease today.

* We would like to thank Sandra Loder for her translation of the primary Winkler text from German to English.